Two Beggars (Lame Beggar Playing a Hurdy-Gurdy and His Wife Singing)

Click on the image to enlarge. Navigate to the other images for different views of the drawing.

Catalogue Number:

53

Artist:

After Adriaen Pieters van de Venne (1589-1662) OR Adriaen Jacobsz Matham’s engraving after van de Venne

Title:

Two Beggars (Lame Beggar Playing a Hurdy-gurdy and his Wife Singing)

Work Type:

Drawing

Date:

early 18th Century copy of 16th Century work

Culture:

Dutch

Medium:

Black ink with washes on laid paper

Dimensions:

11 3/4 in. h X 10 3/8 in. w

Inscriptions & Annotations:

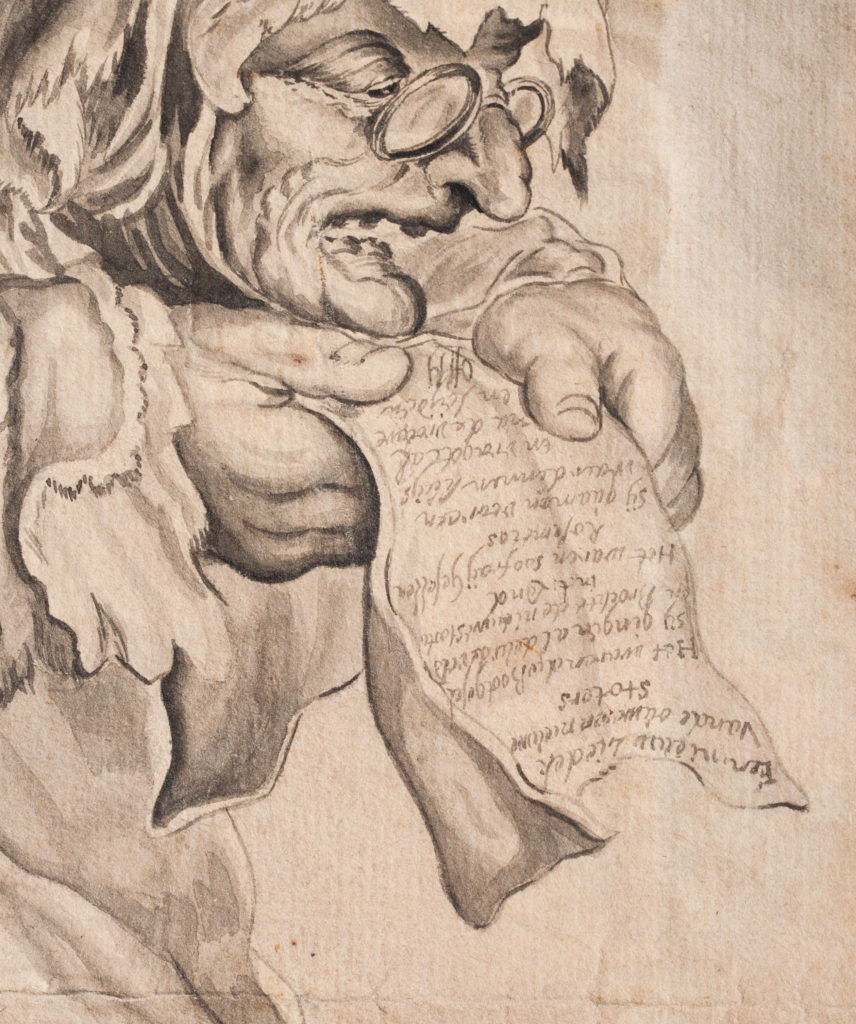

Drawing initialed F or B (ink); Mount annotated Fine & Part Original by Brueghel / Old Drawing (ink) and Dutch watermark (graphite) Verso: Inscribed Brueghel (ink); Verso of mount annotated Mr Mc M / 23 (graphite)

Watermarks:

2 Watermarks; The second one dates the Dutch paper to 1720 (Heawood, 399)

Condition:

horizontal fold/tear at center, scattered light staining and foxing, generally intact and stable

Credit Line:

Cornell College, Gift of Robert Sonnenschein II

Accession Year:

1951

Object Number:

1951.53

Commentary:

The Alasko company initially attributed this drawing of two beggars to the circle of Pieter Brueghel. Through further inspection, the original work is now identified as by Adriaen van de Venne (1589-1662) a Dutch Golden Age painter specializing in allegories, portraits, and political satires. However, through even further digging, the work may also be associated with Adriaen Jacobsz Matham (1590-1660), an engraver and art dealer. Examples of Matham’s seventeenth-century engravings after van de Venne’s work can be found at the Rijksmuseum or the British Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. A painting after the work was also auctioned by Bonhams London in 2004. The engraving includes two columns of verse in Dutch and French; the Dutch inscription states, “Vrijsters hoort wat ick singh en houtet voor gheen leughen, hebie de nieuwe stoters geproest, so sellen de ouwe niet deughen … A. van Venne inven. A. Matham sculp.”

The date for the Sonnenschien drawing was made by looking closer at the details of the paper’s watermark. It tells us that this print is Dutch and from the 18th century due to its popularity during that time period and region. These discoveries also better confirm the possible provenance of the drawing. The drawing, therefore, would not have served as a model for original painting or engraving. Instead, it must be after the original painting by van de Venne (in a private collection) or Matham’s print.

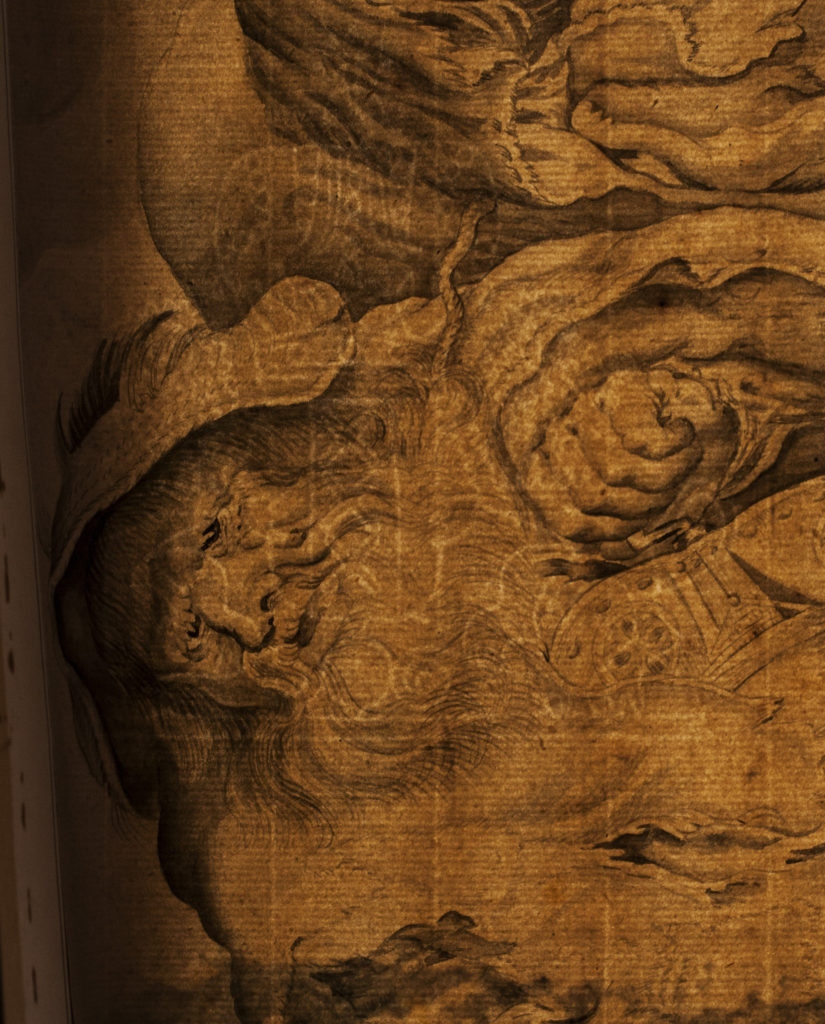

The subject matter of this work portrays two beggars who we assume to be married couple. Based on their clothing which is worn down with holes and dirt, we can conclude that they are not wealthy or well-off in any sense. When taking a closer look at the work, we can see that the male beggar playing a hurdy-gurdy is using a wooden leg to get around; however, based on an observation first made in the catalogue entry at the Rijksmuseum, we see that he does not need to use the leg and assume that he is using it to garner the sympathy of this who may pass by him as he begs for money. The woman is singing a song that is written on a sheet of paper that exclaims how younger lovers are more desirable than older ones. Perhaps this is a clue as to the couple’s troubled relationship? Van de Venne was known for creating Images like this one, and they were not uncommon during this time. It is debatable as to whether these beggars and peasants were real or just the creative liberty these artists took in order to depict how their patrons or clients viewed those with less (van Vaeck and Verberckmoes). The final effect of such subjects was to boost those of higher status by making them feel better about themselves when compared to those of the working class— H.C

M. van Vaeck and J. Verberckmoes, “Who do Beggars Deceive? Adriaen van de Venne, Recreational Literature and the Pleasure of Forging Texts,” in On the Edge of Truth and Honesty: Principles and Strategies of Fraud and Deceit in the Early Modern Period, eds. T. van Houdt, J. L. DeJong, Z. Kwak, M. Spies, and M. van Vaeck (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 269-288.