“Drawings, for good reasons of preservation, are kept locked in cabinets, guarded by their curators or keepers. This protective attitude has effectively kept them segregated, objects somehow precious beyond the paintings or sculptures they often prepare.”[1]

David Rosand’s statement rings particularly true of the Sonnenschein collection, which has rarely seen the light of day—for good reason. The fragile state of these drawings requires that they must be stored in darkness; however, this situation does not mean that the works are any less significant or deserving of attention. The last time that Cornell College’s collection of fifty-eight drawings were examined was in 1997 by the Alasko Company of Chicago. The collection itself was exhibited on-campus only four times: 1966, 1972, 1977, and 1996, and the lack of exposure over the past twenty years has allowed Cornell’s early modern drawings to be overlooked. Some of these drawings deserved to be included in the recent book entitled Seventeenth-Century European Drawings in Midwestern Collections.[2] Yet the authors were unlikely to be aware of the Cornell collection, as the college has not promoted it frequently or fully employed the use of these drawings in our classrooms. This situation is what prompted the conception of a virtual and tangible or physical exhibition of the rarely-viewed college collection of drawings from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century.

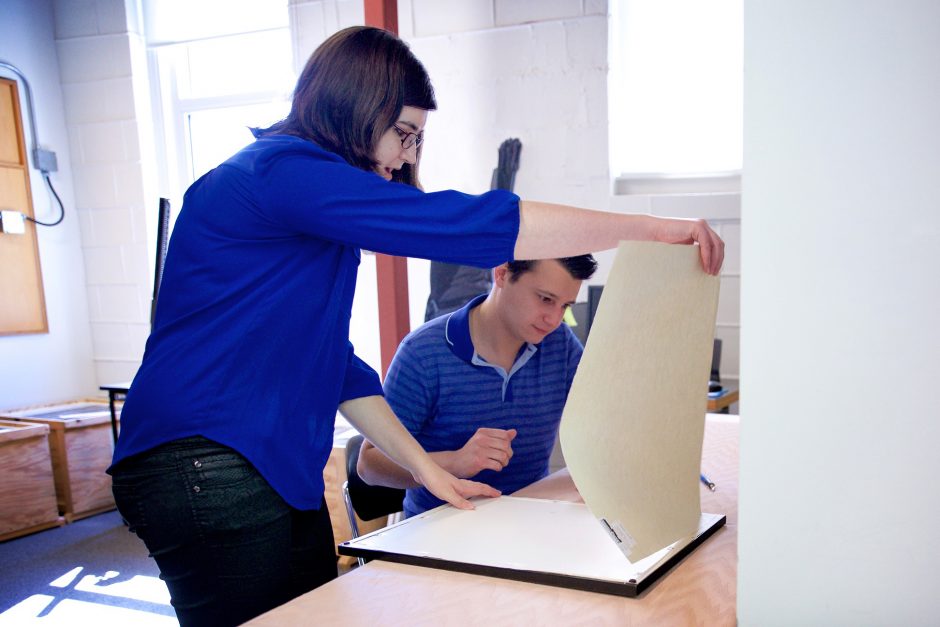

What made these exhibitions possible was funding from the Cornell Summer Research Institute (CSRI) and the Andrew Mellon Foundation. These programs allowed for the support of two students, Steven Coburn and Jessica Meis, to co-curate the show on-line and in the Peter Paul Luce Gallery. The first, a digital exhibition, gives the collection greater visibility without submitting the drawing to more exposure to light. Viewers beyond the campus now can easily view the carefully documented subjects, inscriptions, and watermarks. The documentation provides a newly expanded body of material available for research. Furthermore, new discoveries were made in terms of attributions, provenances, and dating as part of the research process.

The second exhibition, located in the Luce Gallery, allows students to compare the experience of a digital installation to that of the direct encounter with the textures, scales, and surfaces of the actual drawings in physical space. The gallery becomes a classroom to test out the relationship between virtual and physical worlds—a relationship that often engenders some debate on university campuses.[3] As Holland Cotter has argued, something is lost by only viewing the art object from a secondary source and often compares his digital experience today to that of learning about art solely through textbook reproductions.[4]

Any large research project requires the assistance of others, as no publication is truly crafted alone. For this reason, the advice, skill, and support of Devan Baty, Brooke Bergantzel, Rachael Campbell, Susan Coleman, Gregory Cotton, Emily Edwards, Jeff Martin, John Gruber-Miller, Lindsay Alan Parks, José Reyes, Jennifer Rouse, and John Beldon-Scott has been critical.

Christina Morris Penn-Goetsch

[1] David Rosand, Drawing Acts: Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), xxi.

[2] Shelley Perlove and George Keyes, Seventeenth-Century European Drawings in Midwestern Collections: The Age of Bernini, Rembrandt, and Poussin (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 2015).

[3] Mindy Perkins, “On Display: Museum Exhibits in the Digital Age,” Opinion, The Stanford Daily, April 6, 2015, http://www.stanforddaily.com/2015/04/06/on-display-museum-exhibits-in-the-digital-age/

[4] Holland Cotter, “Tuning Out Digital Buzz, for An Intimate Communion with Art,” New York Times, March 16, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/19/arts/artsspecial/tuning-out-digital-buzz-for-an-intimate-communion-with-art.html?_r=0